Do you really think social media invented the need to "clean up one's image" after a mistake? Of course not! In 1830, Eugène Delacroix faced a moral dilemma that would haunt him for years, and his response was to paint the most monumental and symbolic work in French history. Liberty Leading the People is not just a painting about a revolution; it is the testimony of a man who, not daring to wield a rifle, decided that his brush would be his only bayonet. Life is Art, but sometimes, art is the only way we have to sleep peacefully.

The Three Glorious Days and a Paris in Flames

To understand this painting, we must immerse ourselves in the chaos of July 1830. France was at its breaking point. King Charles X, in a desperate attempt to restore the most stagnant absolutism, decided that freedom of the press was a nuisance and dissolved the Chamber of Deputies. It was the spark that set Paris on fire. During three frenetic days, known as the "Three Glorious Days" (July 27, 28, and 29), the streets were filled with barricades, smoke, and blood. The people—from the most refined bourgeois to the poorest child—united to overthrow a monarch who lived with his back to reality.

It was an event that changed the world, but here comes the juicy detail that few mention: while bullets whistled and his compatriots died on the barricades, Eugène Delacroix was safe in his studio. The painter, who always considered himself a man of liberal ideas, felt the weight of his own inaction. He was not a soldier; he was an observer. And that guilt—that feeling of having failed his country at the critical moment—is what permeates every inch of this canvas measuring over three meters.

The "B-Side": Delacroix's Hidden Confession

The story goes more or less like this: Delacroix, tormented by not having physically participated in the fighting, wrote a letter to his brother where he confessed: “If I haven't fought for my country, at least I will paint for it.” This phrase was not a simple patriotic slogan; it was a public apology. The artist needed to redeem himself in his own eyes and in the eyes of history.

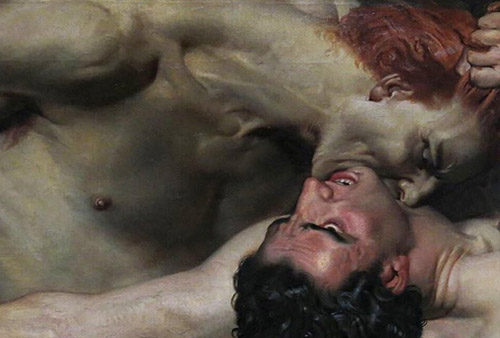

Look closely at the man in the top hat holding a hunting shotgun to the left of Liberty. Traditionally, it has been said that this is a self-portrait of Delacroix. Although experts debate whether the physical resemblance is exact, symbolically it is undeniable: it is the artist placing himself in the scene from which he was absent. He painted himself there, in the midst of the smoke, dressed as a well-to-do bourgeois but ready to die, to claim the place he did not dare to occupy in reality. It is his personal redemption captured in oil.

Marianne: The Strength of a Naked Ideal

In the center of the scene, dominating the compositional pyramid, stands she. She is not a real woman; she is an allegory: Liberty, later known as "Marianne." Delacroix represents her as a powerful, almost superhuman figure, advancing over corpses without looking back. Her exposed chest is not an erotic decision; in classical iconography, nudity represents truth, purity, and honesty. Liberty has nothing to hide.

She wears the red Phrygian cap, the symbol of freed slaves in Ancient Rome, which the revolutionaries of 1789 had adopted as an emblem of emancipation. In one hand, she raises the tricolor flag, which seems to wave with the wind of victory, and in the other, she holds a rifle with a bayonet. This blend of Greek goddess and woman of the people, with underarm hair (a detail that scandalized critics of the time for being "too realistic"), is what makes the work so striking. This is not an ethereal, distant liberty; it is a liberty that smells of gunpowder and sweat.

An Army of Classes: From the Bourgeoisie to the Gutters

Delacroix was very careful in choosing who would accompany Liberty. He wanted to show that the revolution did not belong to a single class, but to the shared will of a fed-up people.

- The Bourgeois: The man in the top hat represents the intellectual and economic class that financed and gave ideological structure to the revolt. He is order joining chaos for a just cause.

- The Rebel Boy: To the right of Liberty, we see a youth with two pistols in hand. He is the representation of the working class and youth. This child is the direct precursor to "Gavroche," the unforgettable character from Victor Hugo's Les Misérables. He symbolizes lost innocence and the reckless bravery of those who have nothing to lose but their chains.

- The Worker: Behind them, men with sabers and simple clothes represent artisans and peasants. There are no pretty faces here; there are exhausted, determined faces marked by the struggle.

Chaos Under Control

The painting is a whirlwind of energy. Delacroix uses a pyramidal composition whose base is the bodies of the fallen. This is a crude detail: liberty is built upon the sacrifice of those who will not see the new dawn. The colors are carefully selected: the red, white, and blue of the flag are repeated in small brushstrokes throughout the painting, unifying the scene under the national spirit.

The background is a haze of smoke and fire where the towers of Notre Dame are barely visible. By placing the scene at a recognizable geographical point in Paris, Delacroix takes the painting out of the world of mythology and anchors it in historical reality. The light does not come from a natural source; it seems to emanate from Liberty herself, illuminating the path through the darkness of the absolutist regime.

Reception and Scandal: The Painting the King Had to Hide

When the work was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1831, it caused an earthquake. The new government of Louis Philippe I bought the painting for the sum of 3,000 francs—not to exhibit it, but to hide it. The message was so powerful and the figure of Liberty so inciting that the "revolutionary" monarch himself feared the painting would inspire the people to take to the streets again.

The work spent years stored in warehouses or in the king's private residence, away from the public. It was not until after the Revolution of 1848, and finally in 1874, that the painting found its permanent home in the Louvre Museum. The painting that was born from one man's guilt ended up being the nightmare of tyrants.

A Legacy Beyond the Canvas

Today, Liberty Leading the People is more than a painting. It is the identity of France. It has appeared on banknotes, on album covers for bands like Coldplay, and has served as inspiration for monuments worldwide, including the Statue of Liberty in New York. Delacroix achieved his goal: although he did not fight in the streets, his painting became the eternal battle cry for any people seeking their emancipation.

It teaches us that, sometimes, the most valuable contribution to a cause is not what is made with the hands, but what is made with the soul and creativity, transforming pain and guilt into a symbol that will last for centuries.

THE WORK

Liberty Leading the People (La Liberté guidant le peuple)

Year: 1830

Artist: Eugène Delacroix

Technique: Oil on canvas

Style: Romanticism

Size: 260 cm × 325 cm

Location: Louvre Museum, Paris

[youtube]9-5XvR0fWJg[/youtube]

[youtube]UjQZ7aqzM0I[/youtube]