The story of Lady Godiva is one of the most well-known medieval legends of England, yet behind the popular narrative lies a complex historical framework that raises fundamental questions about female power, the interpretation of medieval sources, and the way symbolic narratives gradually transform into apparently historical facts.

We had previously published the story of Lady Godiva (you can read it here), but this is a different version with several nuances. The woman we know today as Lady Godiva was probably named Godgifu, a Saxon aristocrat who owned land in her own right. Unlike many later medieval societies, Saxon England allowed certain noblewomen to hold property, make religious donations, and exercise a degree of independent economic influence, which explains her presence in legal documents and land records.

Contemporary historical sources mention Godiva mainly in connection with donations to monasteries and religious foundations, suggesting that her social prestige was closely linked to the patronage of ecclesiastical institutions. This pattern was common among medieval nobility: financing churches ensured spiritual salvation, political legitimacy, and historical memory.

The traditional version of the famous ride first appears in chronicles written more than a century after the supposed events, leading many historians to believe that the episode may have been exaggerated or symbolically reinterpreted. In the Middle Ages, chronicles did not function as modern journalistic records but as moral narratives intended to convey religious or political values.

An alternative interpretation suggests that the term “naked” may originally have meant “without insignia of nobility,” that is, without jewels, ceremonial cloaks, or symbols of rank. In an extremely hierarchical society, appearing publicly without visible signs of power would have been a significant political statement, a symbolic way of identifying with the common population.

Another hypothesis proposes that the story arose from the misinterpretation of monastic records describing Godiva as being “stripped” of her possessions when donating property to religious institutions. Medieval symbolic language, filled with spiritual metaphors, could easily have been reinterpreted by later chroniclers as a literal description.

The element of Peeping Tom also does not appear in the earliest accounts and seems to have been added during the Early Modern popular tradition, probably as a moral warning against voyeuristic curiosity. This detail shows how legends evolve by incorporating new meanings according to the social concerns of each era.

Some scholars have pointed out similarities between the story of Godiva and ancient European pagan rituals that included symbolic processions related to fertility or seasonal renewal. Although these connections are difficult to demonstrate historically, they reflect the medieval tendency to integrate pagan traditions into moralized Christian narratives.

Beyond the literal truth of the narrative, the persistence of the story demonstrates the symbolic power of Godiva’s figure as a representation of aristocratic compassion and personal sacrifice. In the Victorian culture of the nineteenth century, the legend was reinterpreted once again, this time as a symbol of moral purity and female courage, inspiring numerous paintings, poems, and theatrical representations.

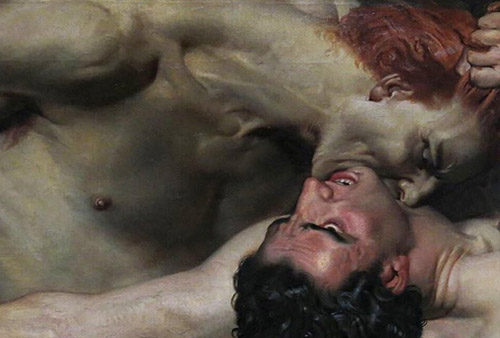

The Artwork

Lady Godiva

Joseph Henri François van Lerius

1870

Oil on canvas

180.2 x 123.7 cm

Private Collection